A landmark study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association on 18 June 2025 links living near heavily microplastic-polluted ocean waters to an increased prevalence of major cardiometabolic diseases. Researchers analyzed data from 152 U.S. coastal counties and found that residents of areas bordered by waters containing over 10 microplastic particles per cubic meter had:

- 18% higher adjusted prevalence of type 2 diabetes

- 7% higher prevalence of coronary artery disease

- 9% higher prevalence of stroke

These associations persisted after adjusting for demographic, socioeconomic, healthcare access, and other environmental factors. The findings raise urgent questions about plastic pollution not only as an ecological menace but also as a public health crisis.

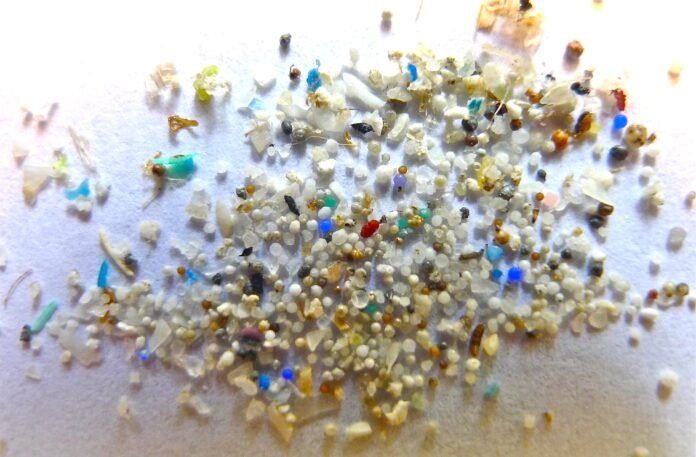

What Are Microplastics?

Microplastics are fragments of plastic less than 5 mm in size—ranging from visible “plastic specks” down to near-invisible nanoparticles. They arise from the breakdown of larger plastic items (e.g., packaging, synthetic textiles, personal care products) and enter marine environments via river outflows, wastewater effluent, and direct dumping. In coastal regions, seawater intrusion pushes these particles into groundwater and even soil, creating a persistent exposure source.

Study Design and Data Sources

Marine Microplastic Assessment

- Researchers obtained marine microplastic concentrations measured between 2015 and 2020 from the National Centers for Environmental Information.

- Measurements spanned the Exclusive Economic Zone (extending 200 nautical miles offshore) adjacent to 152 coastal counties on the Pacific, Atlantic, and Gulf coasts.

- Counties were categorized by mean marine microplastic level (MML):

- Low (0–0.005 pieces/m³): Virtually undetectable

- Medium (0.005–1 pieces/m³): Up to one tiny particle per bathtub-sized volume

- High (1–10 pieces/m³): A handful of small bits per bath

- Very High (>10 pieces/m³): Ten or more particles per scoop

Health Outcome Data

- County-level disease prevalence for type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease, and stroke was sourced from the 2022 CDC Population-Level Analysis, which compiles Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (2019–20) and American Community Survey (2015–19) data.

- Researchers controlled for county demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity), socioeconomic status (education, income, unemployment, neighborhood disadvantage), healthcare access (physician density), and other environmental exposures (air/noise pollution, green space).

Key Findings

Elevated Cardiometabolic Risk in “Very High” Pollution Counties

Residents of counties with very high marine microplastic levels showed significantly greater disease prevalence compared with those in low pollution areas:

- Type 2 Diabetes: 18% higher adjusted prevalence

- Coronary Artery Disease: 7% higher prevalence

- Stroke: 9% higher prevalence

Geographic Patterns

- The Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic coasts exhibited higher cardiometabolic rates compared to the Pacific coast—mirroring the distribution of microplastic contamination.

- Popular tourist and urbanized Gulf-Atlantic regions (e.g., Florida, the Carolinas, Louisiana) often fell into the high and very high MML categories.

Robustness of Associations

- Even after adjusting for traditional risk factors—such as population age structure, poverty rates, and rates of smoking or obesity—the links between microplastic pollution and disease persisted.

- This suggests an independent contribution of environmental plastic exposure to chronic disease burdens.

Potential Biological Mechanisms

While this ecological study cannot establish causation or pinpoint pathways, emerging research offers plausible mechanisms:

- Inflammation and Oxidative Stress: Micro- and nanoplastics can trigger immune responses, generating chronic inflammation—a known driver of insulin resistance, atherosclerosis, and vascular damage.

- Endocrine Disruption: Plastic additives (e.g., phthalates, bisphenols) leach from particles and interfere with hormonal regulation of metabolism and vascular function.

- Translocation and Tissue Accumulation: Recent animal studies have shown nanoplastics cross gut and blood-brain barriers, lodging in organs such as the heart, liver, and brain, potentially impairing function over time.

- Airborne Exposure: In coastal cities, microplastics aerosolized by sea spray and wind may be inhaled, compounding systemic exposure.

Public Health and Policy Implications

Beyond Environmental Stewardship

“This study underscores that plastic pollution is not just an ecological problem—it’s a public health emergency,” says Dr. Sarju Ganatra, senior author and medical director of sustainability at Lahey Hospital & Medical Center. “Communities near polluted waters may be unwittingly breathing, drinking, and eating microplastics that increase chronic disease risk.”

Healthcare Sector’s Paradox

Healthcare itself is a major plastic consumer—from IV bags to syringes and packaging—which ultimately fragment into microplastics. “There’s an irony in healing with plastics that ultimately poison our environment and health,” notes Dr. Ganatra. “We need greener medical technologies and robust recycling.”

Regulatory Action

- Stricter Controls on Plastic Production and Waste: Policymakers should limit single-use plastics, incentivize biodegradable alternatives, and strengthen waste management.

- Monitoring and Labeling: Consumers have a right to know product plastic content; transparent labeling could drive behavioral change.

- Drinking Water Standards: Microplastics currently lack regulatory limits in U.S. tap water—introducing maximum contaminant levels is essential.

Study Limitations

- Ecological Design: County-level analysis cannot demonstrate individual exposure or causation; confounding remains possible despite adjustments.

- Lack of Biomonitoring: Researchers could not measure microplastic burden in residents’ blood, tissues, or diet.

- Unmeasured Pathways: The study assessed only ocean water—microplastics in seafood, drinking water, and air were not quantified.

- Temporal Mismatch: Health data (2019–20) and pollution data (up to 2020) may not perfectly align with disease development timeframes, as cardiometabolic conditions take years to manifest.

Dr. Ganatra emphasizes, “While compelling, these findings demand follow-up individual-level studies before we can definitively link plastic exposure to disease risk.”

Future Research Directions

The authors and accompanying experts outline key next steps:

- Biomonitoring Studies: Measure micro- and nanoplastic levels in human fluids and tissues across diverse populations.

- Longitudinal Cohorts: Track individual plastic exposure (via water, food, and air) and incident cardiometabolic outcomes over time.

- Mechanistic Investigations: In vitro and animal studies to elucidate how plastics disrupt glucose regulation, vascular integrity, and neural control of metabolism.

- Intervention Trials: Assess whether reductions in plastic exposure (e.g., filtered water, dietary changes) translate to improvements in biomarkers of inflammation and cardiometabolic health.

- Policy Impact Modeling: Evaluate public health and economic gains from proposed plastic-reduction policies.

Expert Commentary

Dr. Justin Zachariah, Baylor College of Medicine:

“This county-level analysis is carefully done, but we urgently need individual-level data to guide clinical and regulatory interventions. In the meantime, transparent labeling and consumer awareness can empower people to reduce exposure.”

Dr. Kate Umbers, Western Sydney University:

“The study adds to mounting evidence that even low-level plastic particles can carry health risks. It reminds us that insects aren’t the only creatures harmed by microplastics—humans bear the burden, too.”

Conclusion

As the first large-scale epidemiological signal tying coastal microplastic pollution to serious chronic diseases, this study serves as both a warning and a call to action. Plastic fragments once thought to be benign detritus now emerge as potential contributors to diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. Mitigating this threat will demand cross-sector collaboration—from environmental scientists and clinicians to regulators and industry. The time to act is now, before microplastics become as ubiquitous in our arteries as they are in our oceans.

READ MORE: Higher BMI Significantly Raises Risk of Complications After Bariatric Surgery, New Study Finds