A man in his 50s from northern New South Wales has died from Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV), the state’s first confirmed case. Health officials report the infection occurred months ago after a bat bite and emphasize that “there is no effective treatment” once symptoms manifest. This marks Australia’s fourth ABLV-related death since its discovery in 1996.

The Incident: From Bite to Diagnosis

A patient, unnamed, was treated months ago for a bat bite. He received standard care, including rabies immunoglobulin and vaccine, to prevent lyssavirus. Despite this, he fell critically ill weeks later. NSW Health announced on Thursday that he died from the disease, expressing deep condolences to his loved ones.

Timeline of Events

Several months before hospitalization, a man was bitten by a bat, likely a flying fox or microbat, both carriers of ABLV in Australia. He sought immediate medical care, receiving wound cleaning, antiseptic, and initial rabies immunoglobulin and vaccine. Weeks later, he developed flu-like symptoms, including headache, fever, and fatigue, which quickly escalated to severe neurological issues. He was admitted to a major hospital in northern NSW and spent several days in intensive care as his condition worsened. Laboratory tests confirmed ABLV infection, and health officials announced his death on Thursday.

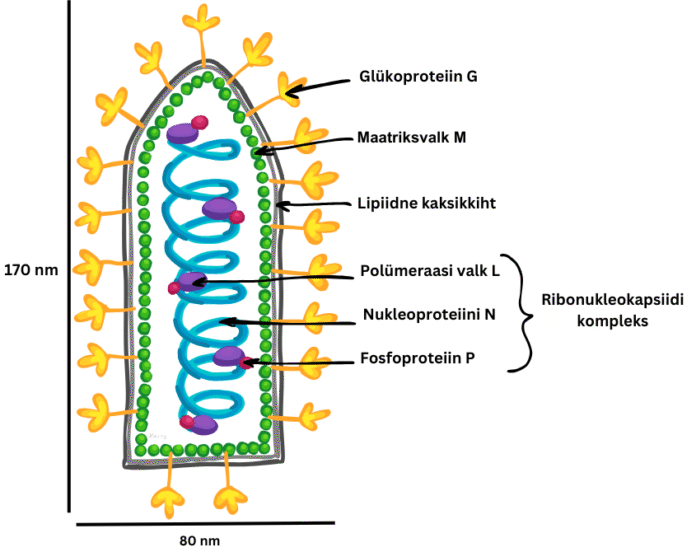

Understanding Australian Bat Lyssavirus

Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV), part of the lyssavirus genus and akin to rabies, was first found in flying foxes in 1996. It has since been detected in all four flying fox species and various microbats. Human transmission is exceedingly rare, but ABLV is nearly always deadly once symptoms appear.

Transmission and Carriers

Flying foxes and microbats primarily carry the virus. It transmits to humans through bat saliva via bites or scratches. Rarely, it spreads indirectly through contact with surfaces contaminated by bats if they touch broken skin. Bats with the virus are found across mainland Australia, from tropical north Queensland to New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia.

Symptoms and Disease Progression

Incubation lasts weeks to months, delaying infection symptoms after a bite. Early signs mimic the flu: headache, fever, muscle aches, and fatigue. As the virus attacks the central nervous system, neurological symptoms appear: confusion, agitation, paralysis, convulsions, excessive saliva, and fear of water. Without treatment, the infection results in coma and death within one to two weeks of symptoms starting.

Public Health Response and Recommendations

NSW Health emphasizes key prevention strategies to reduce human-bat interactions and ABLV risk: Avoid bats entirely, as any bat might carry lyssavirus. Never handle them. If bitten or scratched, clean the wound with soap and water for 15 minutes, apply povidone-iodine, and let it dry. Seek medical help immediately for rabies immunoglobulin and vaccine, as prompt treatment is crucial. Report any bat bites or scratches to local health authorities for proper follow-up and contact tracing.

Historical Context: Previous ABLV Cases in Australia

Since its discovery, human ABLV cases are rare but serious. First two deaths (1996–1998, Queensland): Two women died after bat scratches, with delayed or incomplete treatment. Third death (2002, Queensland): An eight-year-old boy died after playing with an injured microbat, despite initial care. Current case (2025, New South Wales): A man in his 50s is the fourth fatality, first in NSW. These cases highlight that while human cases are extremely rare, with over 100 bat exposures needing medical assessment in NSW in 2024, any bat contact requires immediate medical attention.

Expert Insights on ABLV Management

Dr. Keira Glasgow from NSW Health highlights the urgent need for early prevention: lyssavirus rarely infects humans, but once symptoms appear, treatment is ineffective. Immediate wound cleaning and timely rabies immunoglobulin and vaccine are crucial. Professor Jane Smith from the University of Sydney points out that the long incubation period of ABLV is challenging. Patients might feel fine for months, delaying care if early symptoms are missed.

The Ecology of Bats and Human Interaction

Australia’s bats are crucial for pollination and pest control. However, urban growth brings humans closer to bat habitats, increasing encounters. Flying foxes often roost in urban trees, parks, and gardens. Their migration depends on fruit availability, sometimes traveling hundreds of kilometers for food. Injured bats may fall, leading locals, especially children, to try rescues, risking bites or scratches. Conservation agencies advise against handling bats. Instead, contact wildlife rescue or animal control services for safe management and rehabilitation.

Vaccination and Research Developments

There’s no cure for ABLV once symptoms appear, but research is advancing prevention and understanding of the virus. New rabies vaccines are being developed for longer protection with fewer doses, making them more accessible in remote areas. Antiviral therapies are being studied, but none have worked in humans yet. National programs monitor lyssavirus in bats to guide health advisories. Australia’s guidelines for rabies prevention are updated regularly to include the latest vaccine advancements and global best practices.

Community Awareness and Education

Raising public awareness is crucial to prevent ABLV cases. NSW Health is actively engaging through social media, brochures at hospitals and schools, and training healthcare workers to recognize and manage exposures quickly. Educational programs for students emphasize avoiding bats and reporting encounters to adults. Healthcare workers, including emergency staff and general practitioners, receive regular training on lyssavirus protocols to provide timely PEP. Collaboration between health authorities and wildlife carers ensures safe bat rescue and minimizes public handling.

Conclusion

A man in his 50s from NSW died from Australian bat lyssavirus, highlighting the serious risk of bat exposure and the lack of treatment once infected. Human cases are rare, with only four deaths in Australia over nearly 30 years, but this incident stresses the need for immediate wound care and post-exposure treatment. Health officials urge people not to handle bats, to get medical help after any bite or scratch, and to let trained professionals handle bat rescues. Without a cure, staying alert and acting quickly are our best defenses against this deadly virus.

READ MORE: Aromatic Benzaldehyde Shows Promise Against Therapy-Resistant Pancreatic Cancer