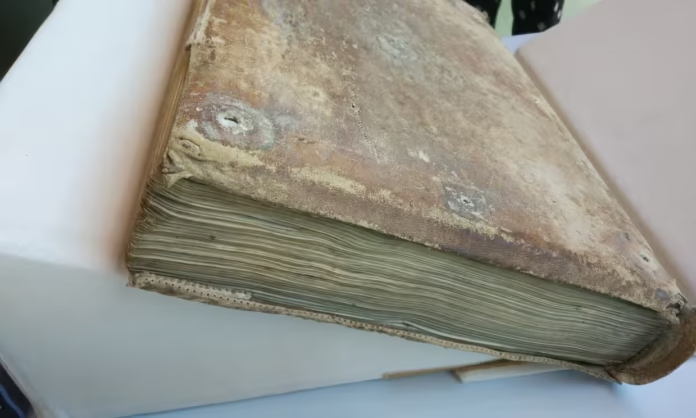

What was once assumed to be the rough hide of deer or boar used in medieval bookbinding has now been revealed to be something much more surprising — sealskin. Researchers analyzing 12th- and 13th-century manuscripts from French monasteries have identified that the covers of dozens of these manuscripts were made from various types of seal, including harbour seals, harp seals, and bearded seals.

International Origins of Monastic Manuscripts

The discovery, published in Royal Society Open Science, shines a new light on the Cistercian monks of Clairvaux Abbey and its daughter houses. These inland monasteries, far from any known medieval seal populations, held books made from skins of seals native to places such as Scandinavia, Scotland, and possibly even Iceland or Greenland.

This points to a vast and previously underestimated medieval trade network. “Contrary to the prevailing assumption that books were crafted from locally sourced materials, it appears that the Cistercians were deeply embedded in a global trading network,” the study says.

READ MORE: Complete Genome Sequences of Six Great Ape Species Unveiled

The Scientific Investigation: Hair, Protein, and DNA

Though earlier library catalogues suggested the covers were made of boar or deer, the researchers grew suspicious when the follicle patterns didn’t match. Detailed protein and DNA analyses confirmed the presence of seal species instead.

“I was like, ‘that’s not possible. There must be a mistake,’” said Élodie Lévêque of Panthéon-Sorbonne University in Paris. “I sent it again, and it of course came back as sealskin again.”

The Mystery of the Missing Records

Curiously, no written records exist of sealskin purchases at Clairvaux Abbey, making the discovery even more remarkable. However, researchers speculate that the monastery’s proximity to Norse trading routes may explain the acquisition. The Norse had established extensive fur and ivory trade networks across the North Atlantic, including with Greenlandic settlements active from the 10th to 13th centuries.

Linking the Cistercians to Norse Trade

The study reinforces the idea of far-reaching medieval trade connections. Cistercians, it appears, were more globally integrated than previously believed. “The findings support the notion of a robust medieval trade network that went well beyond local sourcing, linking the Cistercians to wider economic circuits that included fur trade with the Norse,” researchers concluded.

Aesthetic and Symbolic Choices in Monastic Bookbinding

The sealskin covers, now brown with age, likely weren’t always so dark. The researchers argue that the monks would have preferred the original pale grey or white hue of the skins. Brown was traditionally associated with the Benedictines, the religious order from which the Cistercians separated in 1098, and thus would not have aligned with the Cistercians’ aesthetic identity rooted in white habits and simplicity.

Were the Monks Aware They Were Using Sealskin?

Another layer of mystery surrounds whether the monks actually knew they were binding their manuscripts with seal hides. Since seals were rarely depicted in medieval European art, and given the inland location of the monasteries, it’s possible the monks used the material without realizing its exact origin.

Seals in Medieval and Arctic Cultures

The use of sealskin was well-known in northern and Arctic regions. Seal products served various purposes: the meat provided food, the blubber was used for heat and light, and the skin was crafted into garments and utility items like boots, gloves, and coats.

“In the middle ages, seal exploitation was common in northern Europe and persists in all Arctic cultures today,” the researchers wrote.