Pancreatic cancer is one of the deadliest forms of cancer, and it’s on track to become even more lethal. By 2030, it is projected to be the second-leading cause of cancer deaths globally. Often diagnosed at a late stage, the disease is notoriously difficult to treat, with survival rates remaining dismally low despite decades of research.

But a groundbreaking study from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) offers a glimmer of hope. In a significant advancement in the early detection and interception of pancreatic cancer, CSHL scientists have discovered a potential way to stop the disease before it starts—a concept researchers liken to catching cancer in its earliest whispers, rather than waiting for its full-blown roar.

READ MORE: Major Endometriosis Study Reveals Impact of Gluten, Coffee, Dairy and Alcohol

The research, led by Professor David Tuveson, Director of the CSHL Cancer Center, and Dr. Claudia Tonelli, a research investigator in Tuveson’s lab, may mark a turning point in how we approach one of the world’s most formidable cancers.

“We all have early versions of cancer in many tissues at all times,” says Tuveson. “Think about moles on your skin—some are just moles, some need watching, and a few might need removing. Imagine having that same situation inside your pancreas. That’s the reality. But unlike skin, we can’t see inside our pancreas—until it’s too late.”

Now, Tuveson and Tonelli may have found a way to not only see, but act—before it’s too late.

Decoding Pancreatic Cancer’s Genetic Engine

At the heart of this breakthrough is a deeper understanding of the genetic drivers of pancreatic cancer, particularly the notorious KRAS gene. A mutation in KRAS is present in over 95% of pancreatic cancer cases, making it one of the disease’s most potent accelerants.

But the story doesn’t end with KRAS. The new study, published in the journal Cancer Research, identifies another major player: FGFR2. Long known as a cancer-promoting gene in other malignancies, FGFR2 had not previously been understood in the context of pancreatic cancer.

“We discovered that FGFR2 plays a critical role in amplifying the mutant KRAS signal,” explains Dr. Tonelli. “This synergy makes the early versions of pancreatic cancer more aggressive and more likely to progress into full-blown tumors.”

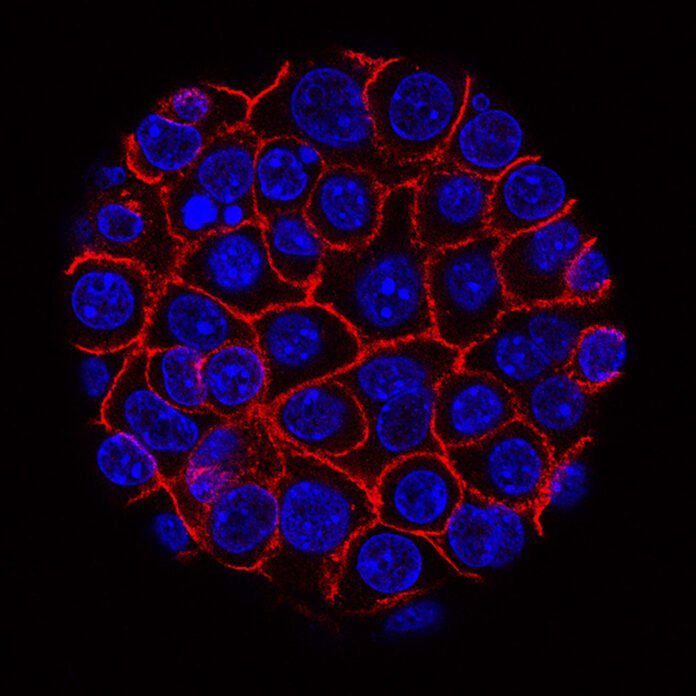

The research used mice models and organoids—three-dimensional, lab-grown replicas of human pancreatic tissue—to simulate how these genes interact and to test methods of intervening at the right moment.

Interception, Not Just Treatment

One of the most exciting aspects of this research is its focus on interception—halting the disease before it turns into cancer, rather than treating it afterward. This concept is especially valuable in pancreatic cancer, where symptoms often appear only after the disease is advanced and harder to manage.

The study’s breakthrough came when researchers applied existing FGFR2 inhibitors—drugs already used in the clinic for other cancers—to pancreatic organoids at a key early stage. The effect was dramatic: tumor formation slowed significantly.

“When we inhibited FGFR2 at precisely the right time, we saw a meaningful reduction in the progression of disease,” Tonelli said.

Then the researchers went one step further. By combining FGFR2 inhibitors with blockers for EGFR—another protein known to be hyperactive in pancreatic cancer—they observed an even greater suppression of tumor initiation.

“Fewer early versions of cancer formed in the first place,” Tonelli explained. “This dual approach could be the cornerstone of a future interception strategy for high-risk patients.”

Implications for High-Risk Groups

The concept of cancer interception could have profound implications, especially for individuals with a family history of pancreatic cancer, or those with known genetic predispositions. These individuals could one day undergo routine screening and receive targeted interventions to prevent cancer from ever taking hold.

“With an increasing number of FGFR2 inhibitors entering the clinic, our study lays the foundation for exploring their use in combination with EGFR inhibitors,” said Tonelli. “For high-risk populations, this could become a standard preventive therapy.”

The idea echoes the preventive use of statins for heart disease or Tamoxifen for breast cancer—commonplace now, but revolutionary when first introduced.

Why Pancreatic Cancer Is So Hard to Beat

Despite years of research, pancreatic cancer has stubbornly resisted most treatment strategies. Its elusive nature stems from several factors:

- It often develops silently, without noticeable symptoms.

- By the time it’s discovered, it has usually spread to other organs.

- It is highly resistant to many forms of chemotherapy and radiation.

- The pancreas’s location deep in the abdomen makes screening and imaging difficult.

Tuveson believes this is precisely why early interception strategies are so essential.

“By the time traditional treatments begin, you’re already several steps behind the disease,” he said. “What we need is a head start. That’s what this discovery gives us.”

A Platform for Future Research

The study also underscores the growing importance of organoid models in cancer research. By allowing scientists to replicate human tissue in the lab, organoids offer an unprecedented window into the earliest stages of disease—a view that traditional methods have long struggled to capture.

Tonelli and her colleagues hope this new tool will accelerate further discoveries—not only for pancreatic cancer, but for a range of other aggressive cancers with limited treatment options.

“We now have a model that can be used to test combinations of drugs before moving into patient trials,” she said. “That’s a huge leap forward.”

Looking Ahead: Turning Science Into Survival

The road from discovery to clinical application is rarely short. But with this new insight into FGFR2 and its role in pancreatic cancer, researchers are one step closer to a future where early detection and targeted prevention could save thousands of lives.

For Tuveson and his team at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, the mission is clear.

“Pancreatic cancer doesn’t give you much time,” he said. “But this research shows that maybe, just maybe, we can get ahead of it. And in the fight against cancer, a head start can mean everything.”